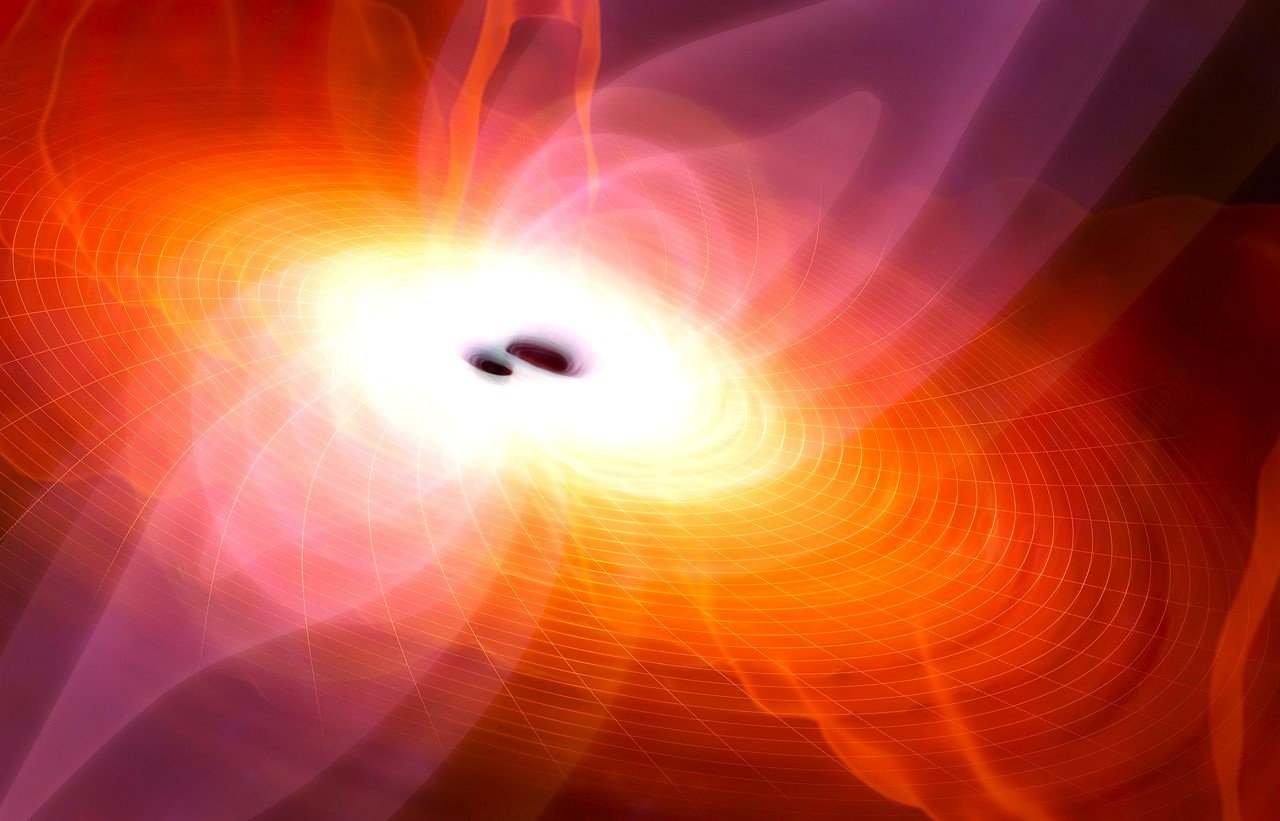

A recent discovery by scientists using the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) has both excited and puzzled astrophysicists. Two colossal black holes—among the largest ever recorded by LIGO—have collided, forming an even more massive remnant that defies long-held theories about black hole formation.

The pair, estimated to weigh in at 103 and 137 times the mass of our sun, fall squarely within a mysterious range once thought to be a black hole “no-go zone.” According to current models of stellar evolution, black holes shouldn’t form between roughly 60 and 130 solar masses. Stars with cores that massive are believed to explode completely in a phenomenon known as pair-instability supernova, leaving no black hole behind.

Yet here they are.

“We don’t think black holes form between about 60 and 130 times the mass of the sun, and these two seem to be pretty much slap bang in the middle of that range,” said Mark Hannam, a physicist at Cardiff University and LIGO team member.

When these two black holes collided billions of years ago, they created a supermassive remnant estimated to weigh between 190 and 265 solar masses—the most massive black hole LIGO has ever detected. The findings, shared in a paper posted to arXiv.org on July 13, add to a growing list of black holes within the so-called “forbidden” mass range, raising fresh questions about how they formed.

A Third Kind of Black Hole?

Until recently, black holes were thought to come in two general categories:

Stellar-mass black holes, which range from a few to several dozen times the mass of the sun, and form when massive stars end their lives in supernova explosions.

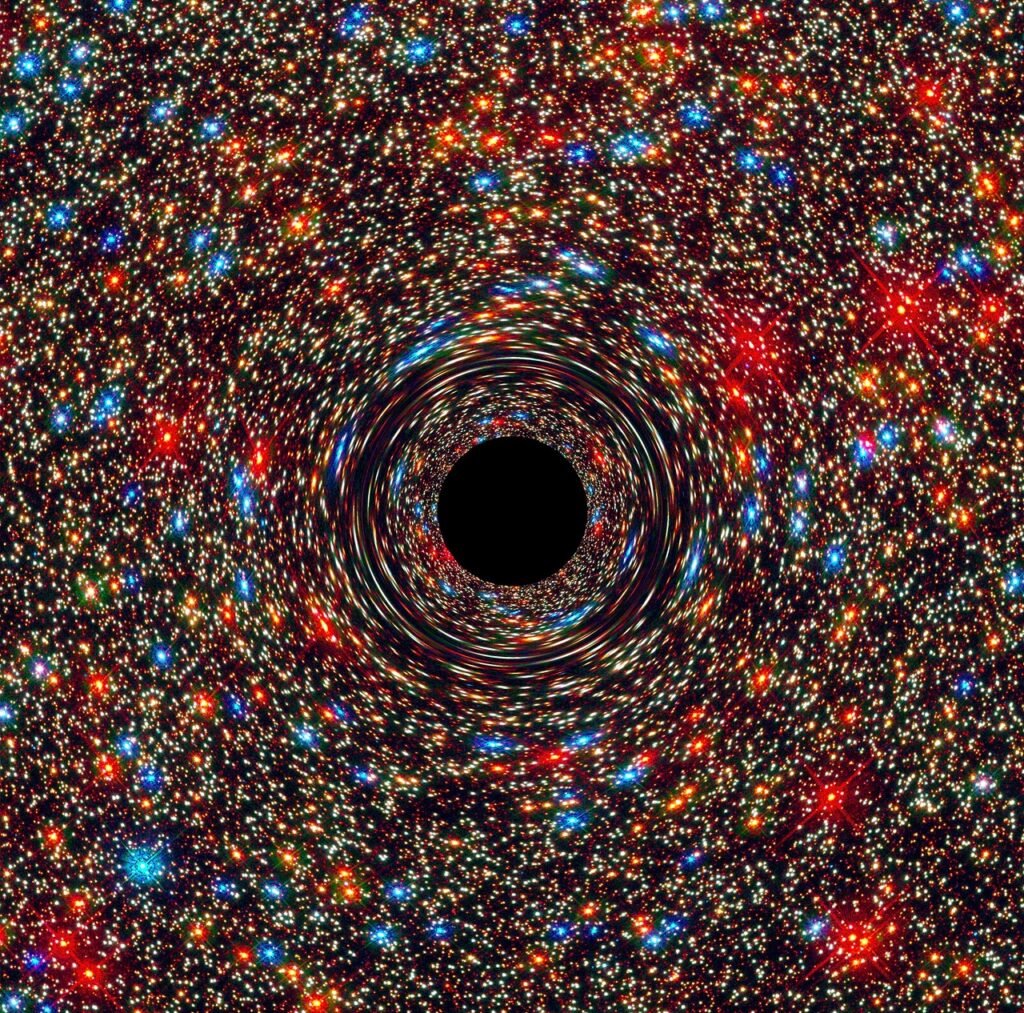

Supermassive black holes, which sit at the centers of galaxies and can weigh millions or even billions of solar masses. These giants appear to play a role in shaping galaxies themselves, but their origins remain one of astrophysics’ biggest mysteries.

This newly discovered collision suggests the existence of a third category: intermediate-mass black holes—those that weigh between roughly 100 and 100,000 solar masses. These elusive objects could be the missing link that explains how small black holes might grow into the supermassive titans found in galactic cores.

A major clue came in 2020, when LIGO observed a merger between two black holes (66 and 85 solar masses) that formed a remnant weighing around 150 solar masses. That detection was hailed as the first solid evidence of an intermediate-mass black hole. Yet even today, theorists continue to debate how such massive stellar remnants could form in the first place.

Rethinking Black Hole Formation

The new discovery deepens the mystery. If black holes aren’t supposed to exist in the 60–130 solar mass range, how did these two form—and how common are they? One possibility is that they themselves are the products of earlier black hole mergers, gradually building up mass over time in dense stellar environments like star clusters.

As LIGO continues to detect more gravitational wave events, astronomers hope to gather enough data to piece together the life stories of these cosmic giants. Understanding their origins may not only help rewrite our theories of stellar death but also shed light on how galaxies—and the universe itself—evolved.

For now, this surprising collision is a powerful reminder that the cosmos still holds plenty of secrets—and black holes are keeping some of the biggest ones.